Demand drivers and freight rates

Iran, Libya and Venezuela face export limitations because of sanctions and internal political troubles. At the same time, US exports of crude oil are growing fast because of pricing and politics.

“We have mobilised all of the country’s resources and are selling oil in the ‘grey market’,” Iran’s deputy oil minister Amir Hossein Zamaninia is quoted as saying by state news agency IRNA, according to Reuters.

Among the main official buyers left, the main ones are China, India and Turkey. BIMCO doesn’t expect that crude oil exports out of Iran will fall much more than they already have – whether “waivers” are in place or not. Exports have averaged around one million barrels per day since US sanctions were reintroduced on 4 November 2018 (source: Lloyds List Intelligence). BIMCO monitors other sources as well to verify what is happening, as it recognises that data on issues such as this come with a high degree of uncertainty.

An official US statement about deployment of an aircraft carrier group in the Middle East, specifically to “respond to any attack from the Iranian regime”, increased tensions to a new high in early May.

The earnings of MRs and LR1s continued to decline as they fell back to loss-making freight-rate levels. In October 2018, the sharp drop in oil prices increased the demand for MRs and LR1s, which lifted earnings. LR2 tankers enjoyed a brief earnings increase in the second half of April, but are still far from the solitary peak at the end of 2018.

A similar story can be told for the crude oil tankers. At the beginning of May, earnings for all crude oil tankers returned to the appalling loss-making levels seen in large parts of 2018. The exception was the VLCCs, which had a short-lived rise in earnings in the second half of February.

In the oil market, global refinery throughput fell by 1.5m barrels per day in March compared with February. The throughput reached a low point in March, but the International Energy Agency (IEA) expects higher throughput in the coming months through to September. Higher throughput is – obviously – positive for oil tanker demand.

The current maintenance season for refineries is more extensive and longer than usual. The extension is likely to indicate an effort to reduce the corresponding maintenance period in the autumn, to capitalise on an expected increase in demand caused by shipping’s switch to low-sulphur fuel.

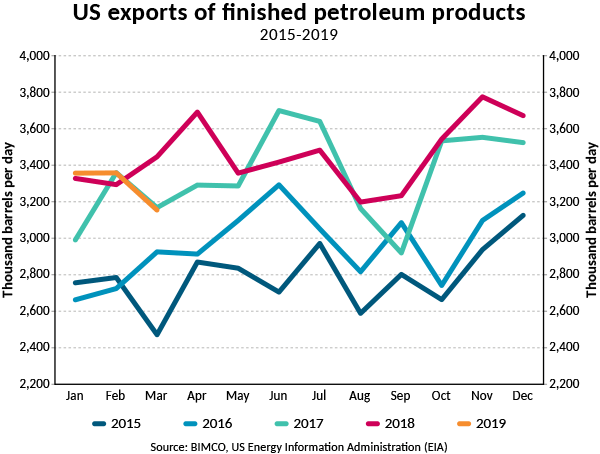

US export of oil products fell by 2.0% in Q1-2019, which was a result of either low export demand or reduced throughput in general.

It also looks like unplanned outages and accidents in the US, which limited refinery throughput in March, may already have reduced export a bit in February.

US exports remain a solid driver of demand for oil-product tankers, despite most of the export destination being shorter haul to South America and Europe.

Fleet news

Why do we focus that much on fleet growth? Because it’s working against a market recovery – and it’s the only fundamental factor that shipowners can affect.

Oil-product tanker fleet grew rapidly in the first four months of 2019. In total, 3.4m dead weight tonnes (DWT) was delivered in that period. That level is a 10-year high, in volume terms, and matches the influx of 2010-11 and 2015-16.

The fleet growth of 1.9% was made up of 14 LR2 tankers, 27 MRs; a couple of handfuls of LR1s and Handysize tankers also entered the active fleet.

The LR2s are mainly used on the medium- to long-haul routes out of the Arabian Gulf, with naphtha for the petrochemical industry going either to North Asia or west, towards Europe.

They all represent a front-loading of new tonnage this year, and as half the expected deliveries have already taken place, BIMCO expects the pace of new deliveries to slow down from here.

This front-loading of new tonnage – combined with a seasonally low demand from February onwards – has only made earnings drop further.

The crude oil tanker fleet grew by 3% in just four months (Jan-Apr). The market got 13.2m DWT of new tonnage, with a limited offset from one million DWT sold for demolition. The participants in the market seem to have very high expectations for a recovery, as the fast fleet growth is only countered by insignificant demolition activity. BIMCO is not so optimistic.

In terms of the number of ships, the market gained 25 VLCCs, 21 Suezmax and 15 Aframax, while one Aframax and three VLCCs left. Currently, 16 of those Suezmax tankers trade in clean cargoes – illustrative of the dynamics of the oil tanker fleet. You cannot be too rigid in your fleet analysis, as these ships can shift between dirty and clean cargoes, depending on market conditions.

There are, fortunately, few new orders for oil tankers. Only 4.7m DWT of oil tanker capacity has been ordered from 1 January through April. The total oil tanker order book was reduced by 10.3% in the same four months. The obvious oversupply of capacity in the market means that no new orders are needed. Despite BIMCO estimates for 2020 and 2021, fleet growth is expected to slow, as few new orders have been placed.

Outlook

The politics are what matters. A business-as-usual scenario in the oil market is only delivering a steady, but not high, demand growth for the oil tanker market. Any upside to the tepid demand growth in 2019 is coming from the IMO 2020 regulation – again, politics – and trades affected by sanctions.

Oil majors are regularly announcing the specs for the range of new compliant fuels they offer to the industry, to comply with the 1 January 2020 deadline – fuel that, once produced, must be distributed. The change in tanker demand because of the fuel switch remains to be seen.

If US sanctions on Iran shifts oil exports to South Korea from Iran and to the Gulf of Mexico, it will have a positive effect on the market. Every VLCC cargo that departs from the Gulf of Mexico for South Korea instead of from Iran is a 150% gain in ton-miles demand.

As an example, a VLCC sailing at 12.5knots spends 54 days sailing 15,000Nm (+5% sea margin) from Houston, US (largest crude oil export port) to South Korea (Busan) – while it takes only 22 days sailing from Kharg Island in Iran to South Korea.

Another potential upside to the crude oil tankers would be a resolution of the US-China trade war – one that would restart Chinese imports of US crude oil. China grew its crude oil imports by 8.1% in Q1-2019, and only a very small amount came from the US. This is, in fact, an increase, as the Chinese cut their US crude-import completely in August 2018. The effect of an end to the trade war on the markets would be similar to those of US-Iran-South Korea, because of the proximity of China to South Korea.

After rapid growth in 2017, when annual US oil-product exports grew by 12.5% (372,000 barrels per day), exports grew by only 3.3% in 2018. Of the incremental growth in 2018, 44% (156,000 barrels per day) was distillate fuel oil (15, or below, parts per million [ppm] sulphur content).

The US distillate fuel oil is exactly what the shipping industry needs to burn to comply with the sulphur limit that takes effect from January 2020. If US refineries can further optimise their production towards distillate fuel oil – which would then be redistributed around the world to bunker hubs – it would be another positive factor for tanker demand.